Scientists use radio telescope to reliably see newly born planets

Peering into galaxies far, far away is a herculean task. Take the James Webb Space Telescope, for example — the contraption that today offers some of the most incredible views of the early years of the universe took nearly three decades of planning to become functional today. Yet, even for James Webb, some sights of the solar system remain difficult to attain — such as viewing just-born planets.

That is exactly what the scientists at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics claim to have achieved, through a new series of observations that have been made since 2019 through the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA) ground radio telescope.

Using observations through ALMA, a team of scientists led by Feng Long at the Harvard-Smithsonian institute used the data to observe LkCa15 — a protoplanetary disc that is 518 light years away from us.

These observations have helped Long’s team make a note of two constant ‘lumps’, which were orbiting within a distance of 42 astronomical units — 6.3 billion kilometres. One astronomical unit, for reference, equates to 150 million kilometres, and is the distance between Earth and the Sun.

These lumps, after being run through a number of astronomical computing models that are used to study observations made by space and ground telescopes, appeared to be consistent with the properties of a planet. This, therefore, signified one of the first instances of a newly formed planet being studied closely and in deeper detail than before.

Explaining what the problems have been with studying newly born planets, Long said in a statement, “Directly detecting young planets is very challenging and has so far only been successful in one or two cases. The planets are always too faint for us to see because they’re embedded in thick layers of gas and dust.”

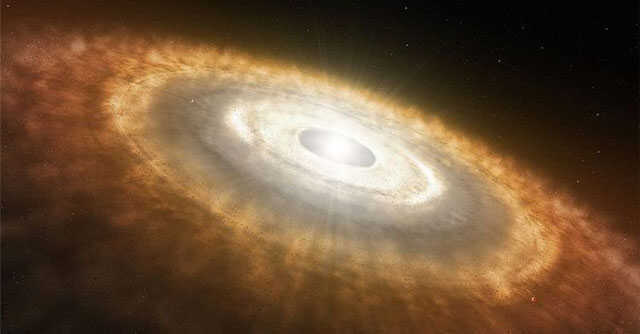

Long explained that over the past few years, researchers have seen various structures that could have signified planets within protoplanetary discs — which are clouds of dust and gas surrounding a newly formed star, which fall in the planet forming belt of a star. Over time, which is billions of years, this belt leads to the formation of multiple planets, and in the eventuality, a solar system.

The new research system has helped the researchers achieve a closer study of planet formation within these discs — a potentially breakthrough achievement to locate early stage planets.

These early planets can help researchers understand the conditions of the formation of a planet, which could in turn help humankind identify conditions that may lead to the creation of a potentially habitable world. Eventually, this material can help scientists narrow down with more precision on exoplanets that could exhibit life supporting conditions, too.

The study was published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters. Long, on the other hand, will be joining the NASA Hubble team at the University of Arizona, for further work on space research.