Faqir Chand Kohli — the ‘Headmaster’ that TCS needed

The creation of Tata Computer Centre in 1965 ushered in a period of aggressive selling and business began to look up. It had been set up in in Nirmal building at Nariman Point, then a developing area reclaimed from the sea in South Bombay.

From 1968, the unit undertook a lot of banking work, mostly reconciling inter-branch accounts, payroll accounting and head office accounting. The volume of banking work was so large that by the mid-70s, there were 500 professionals in Delhi and other places where the Tata Computer Centre had IBM/ICL machines. International Computers Ltd was a leading British computer company, which was second to IBM in the Indian market.

Up until this point, Tata Sons had very small holdings in Tata group companies, and their earnings were mainly dependent on dividends paid by these companies. To enhance income, the Tatas decided in 1968 to restructure some of the units as operating divisions.

Four separate divisions were born at one go: Tata Consulting Engineers, Tata Economic Consultancy Services, Tata Financial Services and Tata Consultancy Services (TCS). The Tata Computer Centre became a part of TCS, and P M Agarwala, managing director of Tata Electric Companies, took over as ‘Director In Charge’ of TCS in addition to his other responsibilities.

Agarwala, or PMA as he was often referred to, was one of India’s earliest telecom/ electronics engineers from Roorkee University (now IIT Roorkee), and was a technical member of the Government of India’s Posts and Telegraph and Telephone Board before joining Tata Electric.

The young, highly talented team of TCS was often more like a rowdy, boisterous bunch from the Wild West. Every new order created euphoria and each invoice was celebrated with a beer party on the terrace of Nirmal building. Winning a contract warranted a movie in the afternoon at one of the nearby theatres. Spirits were running high but the same could not be said about the cash flow. Agarwala was quickly seized of the situation and realised that he needed a strong hand at the top—a ‘headmaster’ figure—to bring in order.

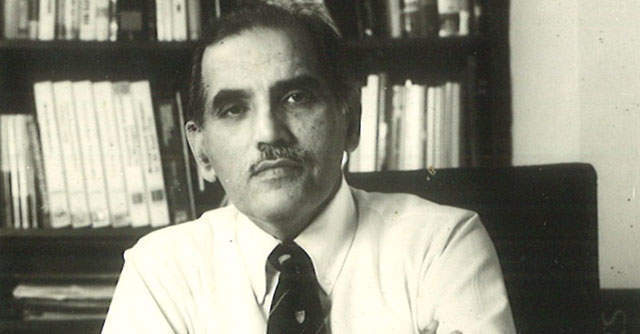

He chose Faqir Chand Kohli, a brilliant technocrat who was deputy general manager at Tata Electric. His role as chief load despatch meant that he controlled the power grid for the city of Bombay. Agarwala perhaps felt that if Kohli controlled the power to the entire city, surely he could control the unruly lot at Nirmal building.

Kohli was also knowledgeable about computers and that too would have been an influence on his choice.

There was just one problem. Kohli did not want to leave Tata Electric and viewed a move to TCS as a diversion from his ambition to ultimately head Tata Electric which at that time was a prestigious post.

But Agarwala prevailed and despite his reservations, Kohli was coerced into joining TCS as general manager in 1969: a post that was specially created for him. The adjustment to the new environment took him six months. He would pore over technical manuals at home to acquaint himself with technology, thereby earning the respect of his juniors. This held an important lesson for me that, as a leader, one must have a strong working knowledge of the technical environment that one is managing.

Finally, Kohli began to integrate with his new team and a new selling strategy started to emerge. Since neither the government nor private companies were interested in data processing, the TCS team decided to position the company as management consultants.

Green Shoots

This new positioning opened the doors to new business: once the client was engaged, they were encouraged to take on automation and electronic data processing work as a way towards more efficient management. This was a convoluted route to data processing work but was necessary since, manual systems being prevalent, automation at that time was not very well understood. So ironically while TCS began with data processing and moved to management consulting, western management consulting companies on the other hand were diversifying into IT services.

Once Kohli had settled into his new role at TCS, he set about shaping the young company armed with the conviction that in order to use computers, India needed bright young people with good education—something India had in abundance.

Kohli had a good relationship with the IITs (Indian Institutes of Technology) where he used to teach often. He capitalised on this to recruit the best and the brightest young engineering graduates.

When TCS was formed in 1968, there was no separate IT departments in Indian universities. Indian electrical and electronic engineering graduates, with an interest in IT, typically went overseas to undertake their graduate studies in computer science. Under Kohli, TCS recruited most of the first batch of students who had completed their Masters in computer science at IIT Kanpur, one of India’s premier technology institutes and the first to introduce computer science doctoral studies—although at that stage it was still under the electrical engineering department. Other early IIT Kanpur graduates went on to set up many of India’s other IT industry start-ups.

In those days, it was as though TCS was a Silicon Valley start-up. Here was a group of India’s brightest people with no dictated agenda and, because we were a division of Tata Sons, there was no requirement to produce a balance sheet.

Management consultancy was becoming big for TCS. It involved working with government organisations like Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL), providing major production planning and control systems for light combat aircraft. These were very complex systems and spoke of the strong expertise TCS had.

A major system engineering and cybernetics activity was set up with the help of George Mason University who helped with the training. The training was on the simulations systems used in the US for war games; TCS’s interest was in using these very applications with changed variables, to solve societal problems. Later, a centre in Hyderabad was set up for these services.

One of the earliest organisations TCS worked for was the Delhi Development Authority (DDA), helping them in their corporatisation with a focus on societal benefit. Similar work was done for the Government of India’s Department of Atomic Energy around the time that the Nuclear Power Corporation of India was being formed as a public sector company. TCS also worked with the north-eastern states to try and figure out why government aid was not reaching down to the people.

The management consulting work established our intellectual leadership and helped position TCS as a thought leader.

At the Helm

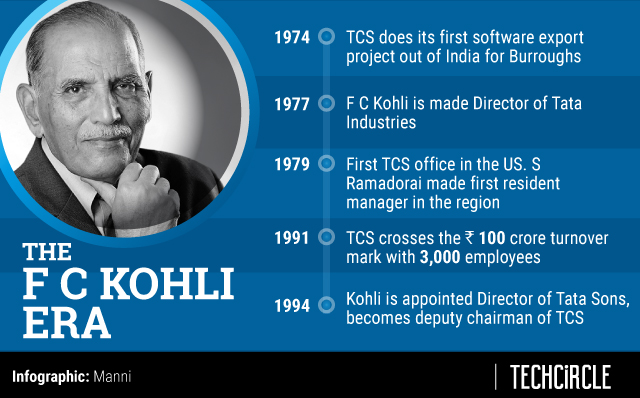

In 1974, when Kohli was still general manager, Agarwala took ill and began to operate from home. Unfortunately, he did not recover and succumbed to his illness a few months later. Kohli took over as TCS Director In Charge the same year. He reported to the TCS Consultancy Committee whose members were Tata Sons directors: A B Billimoria, Freddie Mehta and Nani Palkhivala, who was also chairman of the committee.

For the first time, Kohli was in a position to drive TCS’ vision. From general manager to Director In Charge was a big jump. In the normal course of things, had Agarwala lived through his term, Kohli may well have returned to Tata Electric.

Armed with an electrical engineering degree from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Kohli had already earned a reputation as a visionary. His early contributions at Tata Power included the use of control system methodologies to provide a stable power supply system for Bombay.

At Tata Electric, he introduced advanced engineering and management techniques, and made significant use of digital computers for power system design and control. In 1968, ahead of all but four utilities in the US, Tata Electric installed a Westinghouse computer to control the operations of its power grid which comprised three hydro stations, thermal units and energy supplies from the Tarapore atomic energy and Koyna hydroelectric stations at the Maharashtra State Electricity Board.

What Kohli realised was that monitoring and controlling were critical to the provision of a reliable power supply. He Clearly understood the power of technology.

Kohli always wanted India to be part of the computer revolution that was beginning in the West. His electrical engineering degree and MIT training coupled with his voracious appetite for books on technology gave him the confidence to try new things in India and to create value.

I often wonder what might have happened if Kohli had stayed at Tata Electric. Perhaps he would have enabled great transformations in the power sector with his zeal and enthusiasm for applying new technologies to the generation and transmission of power.

All that he gave to the IT industry would have gone instead to the power sector. Perhaps he would have built up a huge talent base that would have met the Indian government’s mission of power for all by 2012. Unfortunately todays, sectors such as these face a huge shortfall of good people and leaders to drive the agenda aggressively.

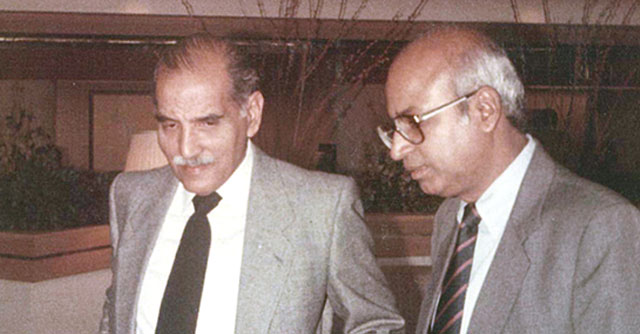

F C Kohli with S Ramadorai in 1990 | Image Credit: S Ramadorai

When I joined TCS in March 1972, I got to know my mentor F C Kohli for the first time. He was actively involved in recruitment and used to meet every new recruit.

Most young entry-level engineers were afraid to approach Kohli because of his reputation as a stern taskmaster. But our initial trepidation began to go away as we started to learn a little more about him and realised that he was a man who was very direct and very quick to grasp issues.

He would tell us quite bluntly what was the right thing to do, and what was not. However, if you were sure, you could challenge him, and he would respect that. Most importantly, he taught me the importance of under-promising and over-delivering to clients. He was always willing to help you succeed if you were willing to put in the work.

When Kohli spoke, you listened, which taught me the importance of being a good listener. But he was also a man of few words and his instructions were often quite minimal, which trained me to anticipate what was required to be delivered.

This edited excerpt from The TCS Story & Beyond by S Ramadorai has been published with permission from the author. Ramadorai was managing director and CEO of TCS from 1993 to 2009, and served as its vice-chairman until 2014.