From groceries to e-tailing, hyperlocal delivery startups back in the limelight

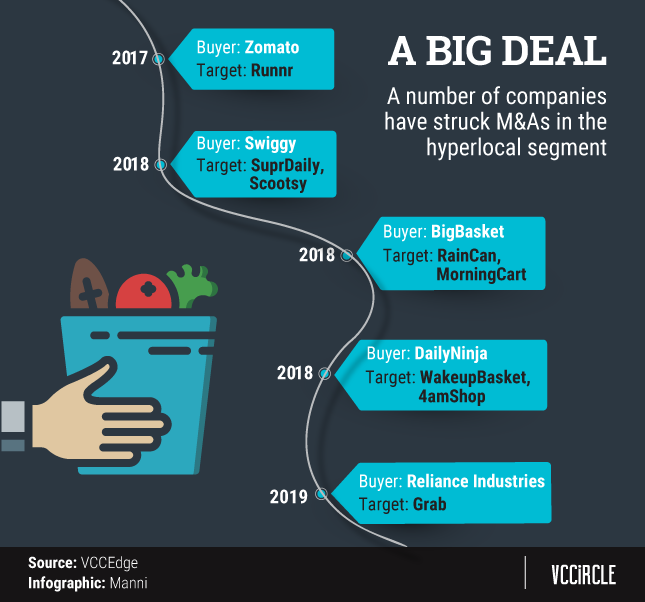

Last month, food-tech unicorn Swiggy started offering home delivery of groceries and other daily essentials. And last week, Reliance Industries Ltd agreed to acquire a majority stake in Mumbai-based Grab. The two developments add momentum to a trend that showed early signs of activity last year—the dramatic turnaround of the hyperlocal delivery services market in India.

Swiggy and billionaire Mukesh Ambani-led Reliance, however, are not the only ones betting big on hyperlocal services. Online grocers BigBasket and Grofers, big e-commerce companies such as Amazon, and a bunch of startups such as MilkBasket, DailyNinja and Dunzo are all taking a shot at a market that was in turmoil less than two years ago.

The hyperlocal delivery segment had seen a number of startups emerging and attracting marquee investors during the funding boom of 2014 and 2015. But most of those shut shop in 2016 and 2017 due to a variety of factors including a lack of sustainable business model, wafer-thin margins, high logistics and customer acquisition costs, and fierce competition.

A tightening of purse strings by investors only made matters worse. Heavily funded startups such as PepperTap and LocalBanya along with Gurugram-based LazyLad, Nagpur’s GetNow.at, Delhi’s AAGAAR.com and Mumbai-based MovinCart were among the ventures that shut operations. Grofers downsized its operations while e-commerce giant Flipkart closed its grocery delivery app Nearby and ride-hailing company Ola shut its hyperlocal delivery service Ola Store.

“The first attempts to crack the market were made in 2015. Everyone jumped at the opportunity, tried different business models and expanded in various cities,” says Mrigank Gutgutia, a consumer technology consultant at RedSeer Management Consulting Pvt. Ltd. “But in 2016, once the funding stopped, many players shut down or pivoted. It was the first stage of failure of experimentation.”

Since then, however, the hyperlocal segment has overcome the phase of self-doubt and investor apathy. Big investors like Japanese conglomerate SoftBank Group Corp and Chinese e-tailer Alibaba Group Holdings Ltd have pumped in millions of dollars in Grofers and BigBasket, and new players such as Reliance, Swiggy and Zomato have entered the segment by making acquisitions. BigBasket last year raised $300 million in a funding round led by Alibaba whereas Grofers secured $60 million in a round led by SoftBank.

Revival of interest

Industry executives say that, until a couple of years ago, the hyperlocal delivery segment was not ready for aggressive expansion. “Many players became aggressive by launching operations in 20 cities and gave heavy discounts. This backfired, especially after the funding environment took a turn for the worse,” says Gutgutia.

The funding crunch prompted some startups to refine their business and supply-chain models in a bid to survive the turbulence. These included Bengaluru-based logistics startup Shadowfax Technologies Pvt. Ltd and Gurugram-based micro-delivery grocery venture Milkbasket. Interest in hyperlocal delivery gained momentum after December 2017 when technology giant Google invested in Dunzo in its first direct India investment. Dunzo, which also counts Blume Ventures as an investor, allows users to create to-do lists and fulfills tasks such as grocery and restaurant deliveries through its chat-based app.

Shadowfax, which counts International Finance Corporation among its investors, initially started out as a food-only delivery player but has diversified over the years. It now provides intra-city logistics services to neighbourhood merchants, grocery shops, pharmacies and e-commerce companies. Co-founder Vaibhav Khandelwal says a strong focus on the business model to manage a distributed workforce and algorithm engines have helped Shadowfax scale smoothly.

Milkbasket, which raised $7 million in an extended Series A round late last year, positions itself as the online version of local mom-and-pop grocery stores but with almost 5,000 stock-keeping units.

Milkbasket co-founder and CEO Anant Goel says the startups that existed in 2015 were trying to fulfill customer demand in 60 to 90 minutes. “That model is unsustainable. One cannot make money by supplying groceries to customers in 90 minutes,” he says.

Goel says Milkbasket’s fundamentals and unit economics are different than those of hyperlocal players that failed. “We manage inventory in house. Our cost of delivery is very low because we deliver in morning hours. For us, every order is profitable.”

Industry executives say many startups have now proven their business models and understood the nuances of consumer behavior. This has led to renewed interest from not just financial investors but also from e-commerce and food-tech companies.

For instance, Amazon’s grocery service Prime Now delivers perishable items as well as home and kitchen products in Bengaluru, Delhi, Mumbai and Hyderabad. Flipkart launched its grocery service Supermart in August 2018. Swiggy, BigBasket and hyperlocal delivery startup DailyNinja have each made two acquisitions. Swiggy acquired Scootsy Logistics, which delivers food and apparel, and milk delivery startup SuprDaily. Zomato bought Runnr while DailyNinja took over Hyderabad startups 4amShop and WakeupBasket.

“Business models are more refined now. Unit economics and supply chains are improving as more people are ordering food online. The market is more ready for hyperlocal delivery services compared to three years ago,” says Gutgutia.

Gutgutia also says that there is traction in all three types of hyperlocal delivery categories—large grocery players like BigBasket and Grofers; horizontal players such as Flipkart and Amazon; and emerging verticals like milk and meat delivery startups.

“Maturity in the food-tech and e-tailing sectors along with improving supply chains and consumers’ general comfort with online shopping has led to a boom in the hyperlocal segment,” Gutgutia adds.

Challenges, opportunities

According to a recent report by RedSeer, the online grocery market is likely to continue chugging along at 50% growth rate for the next few years. The market will be served by companies operating on various models. These would include category specialists, large vertical players as well as horizontal e-commerce companies.

However, the market is top-heavy. BigBasket and Grofers alone account for three-fourths of the grocery delivery market. And both companies are gaining strength. Both raised fresh funding last year, grew their net sales and pared their loss.

Still, some believe that companies are only scratching the surface of the growing market for hyperlocal delivery services and that there is plenty of scope to grow for more than a few companies.

Ashish Fafadia, partner at Blume Ventures, says that more “patient money” is the need of the hour to support startups for a long run and enable them to find the right product fit. However, the sector does have a lot of room for consolidation as larger companies will try to maximise their reach, he says. But for consolidation to be successful in a divergent market like India, companies should focus on the supply chain and should have the ability to handle varying needs of the same customer, he says.

“This sector can allow a smaller company to come back from behind and do well in a highly specialised vertical. “Larger funded companies may be better suited to acquire companies and let them build rather than throw capital and build in house,” he says.

Fafadia also says the hyperlocal market is even bigger than the e-commerce market. “In an e-commerce business, you can have warehouses at certain locations and just have to make sure that supply chain and logistics are taken care of,” he says. “In hyperlocal, many algorithms are connected. It is not a winner-takes-all kind of a market.”