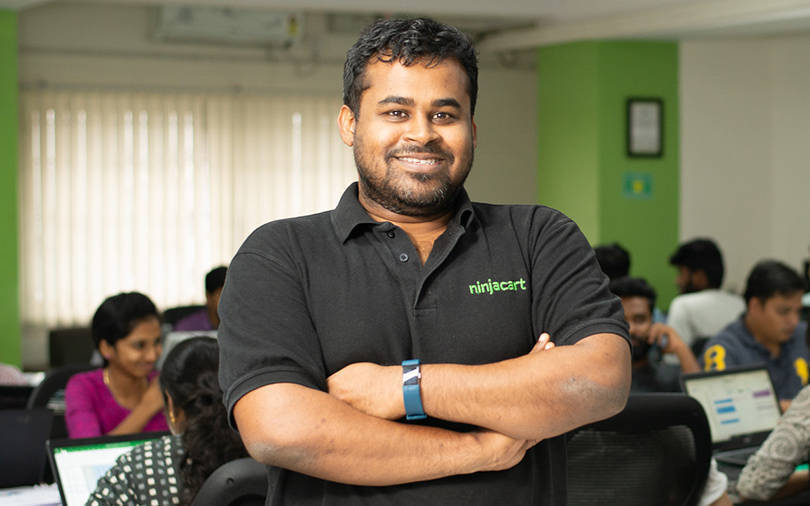

Ninjacart CEO on the agri-tech startup's mission to be a one-stop solution for farmers

The founders of Bengaluru-based agri-marketing platform Ninjacart have a very simple but daunting mission at hand—removing inefficiencies in the business-to-business agri-supply chain.

Validating the company’s efforts to this end is a $35-million cheque it recently raised as part of a Series B funding round led by US-based Accel and Switzerland-based agri investor Syngenta Ventures.

The company, which counts Nandan Nilekani, Japanese VC firm Mistletoe and others as investors, was founded in 2015 by Thirukumaran Nagarajan, Kartheeswaran KK, Sharath Loganathan, Ashutosh Vikram, Sachin P J and Vasudevan Chinnathambi, all of whom have had prior stints at Commonfloor, OlaCabs, HT Media, Verizon Labs, Taxiforsure, and others.

The firm’s agri-marketing platform allows farmers to sell vegetables and fruits directly to business establishments such as shops, retailers and restaurants. The three-year-old venture originally started out as a hyper-local grocery delivery company but then pivoted to the present B2B setup.

In an interaction with TechCircle, co-founder and chief executive Nagarajan spoke about how it will use the fresh capital it raised, the company's road ahead and the current landscape of the agri-tech space. Edited excerpts:

How will you use the latest round of capital?

The funding will be used for three broad purposes. First is geographical expansion. We are currently present in three cities—Bengaluru, Hyderabad and Chennai. Our next port of call is Mumbai and Delhi. There is a lot more opportunity and challenge in these two markets, not to mention the learning curve. After that, we will look to get into other cities.

Secondly, a part of the money will also be used to develop our product and technology, and thirdly, we will augment our supply chain infrastructure

What’s next for Ninjacart?

Once we enter the major metros, we want to create satellite cities. For example, after we launch in Mumbai, we will look to expand to Pune, Ahmedabad and Nashik. Likewise, when we enter Delhi, we will venture into NCR, and after Bengaluru, we will look at Mysore, Hubli and Dharwad.

The broad intention is to optimise the supply chain. Geographical expansion entails higher purchase power. Over the next two years, the focus is on geographical expansion and becoming profitable in each of these cities.

Give us an overview of your operations and the current size of your farmer and buyer network.

In the Bengaluru market, we work with 22 villages and have a collection centre in each of them. The farm produce goes to fulfilment centres in the outskirts of the city. We have two such for the Bengaluru market, measuring 20,000 square feet each. From here, it goes to the distribution centres located in the cities.

We have around 4,500 farmers on our network. On a monthly basis, around 1,100 farmers transact with us. The Bengaluru market currently accounts for our primary business. The reception for new ideas in this space is also better in this zone.

On the buyer side, about 4,000 stores buy from our platform and we fulfill about 2,500-2,600 orders. On a daily basis, we currently handle a little over 300 tonnes in our three markets, with Bengaluru accounting for over 200 tonnes currently.

Do you plan to expand your warehousing capabilities?

Ramping up the fulfillment centres is not really the need of the hour as the produce only passes through these centres. But we are setting up cold storage facilities for certain kinds of high-quality fruits. However, as we expand our operations further, we will open more collection centres.

What pain points and inefficiencies is Ninjacart trying to address?

We try to act as a one-stop solution for the farmer, where we take everything from procurement to payment.

We have also started other initiatives with the farmers such as sharing knowledge on advancement techniques in maximum yield per acreage and advising them on the ideal crop rotation cycle for better land utilisation and revenues. Besides, we share our prediction and analysis on demand and pricing.

We select a few model farmers from every region, who have benefitted from this initiative and use them to educate their peers on the best agricultural practices and to try out new crops.

As part of this programme with the farmers, we provide them with seeds, fertilisers and even money for labour. The arrangement is that they follow the prescribed agricultural practice to make the produce risk-free. We take responsibility for any damages sustained in the process. But when the harvest yields abundant produce, we sell it, take back our investment and share the profit from the sale with the farmer. Around 200-300 farmers on our network are part of this programme.

For retailers, particularly the smaller ones, buying through Ninjacart is convenient and helps them save on logistics costs. Smaller retailers are at the heart of our business.

How do you procure produce from farmers?

We have a farmer-facing app. Our field agents reach out to farmers directly and advise them on the weekly production needs in advance. Accordingly, our system automatically allocates and notifies them of the harvest schedule and the delivery time, so that the concerned farmer may reach the procurement point in time.

Tell us about the agri-tech space in India.

As a market, India was broadly seen as urban and so everyone focused on that. However, three to four years ago, a number of startups started addressing agriculture. With the increasing adoption of mobile phones, farmers were getting more connected and were looking to access services catering to the urban audience.

Besides agriculture, a lot of innovation—in terms of quality and distribution—has to come into sectors like poultries, meat and fisheries industry.

Fintech for rural India is a hitherto unexplored area. Thanks to Aadhar and the Unified Payments Interface, there is renewed interest to bring fintech to farmers. Most of them have a bank account. The question now is how to make them more bankable as capital expenditure is required by this community as well.

Tell us about the competition in this sector.

The opportunity is humungous. To give perspective, Bengaluru alone needs 15,000 tonnes of vegetables and fruits per day and we are addressing just 220 tonnes. So, I believe many more companies can co-exist in this space and can become profitable.

While I do not recollect names, I have read about startups coming up in precision agriculture, vertical farming, drone agriculture, shelf-life improvement, disease prediction and yield improvement through satellite imagery, etc.