For bus aggregators, the road to maturity has plenty of speed bumps

This is the second of a three-part series that analyses India's transport aggregation sector. You can read the first part here.

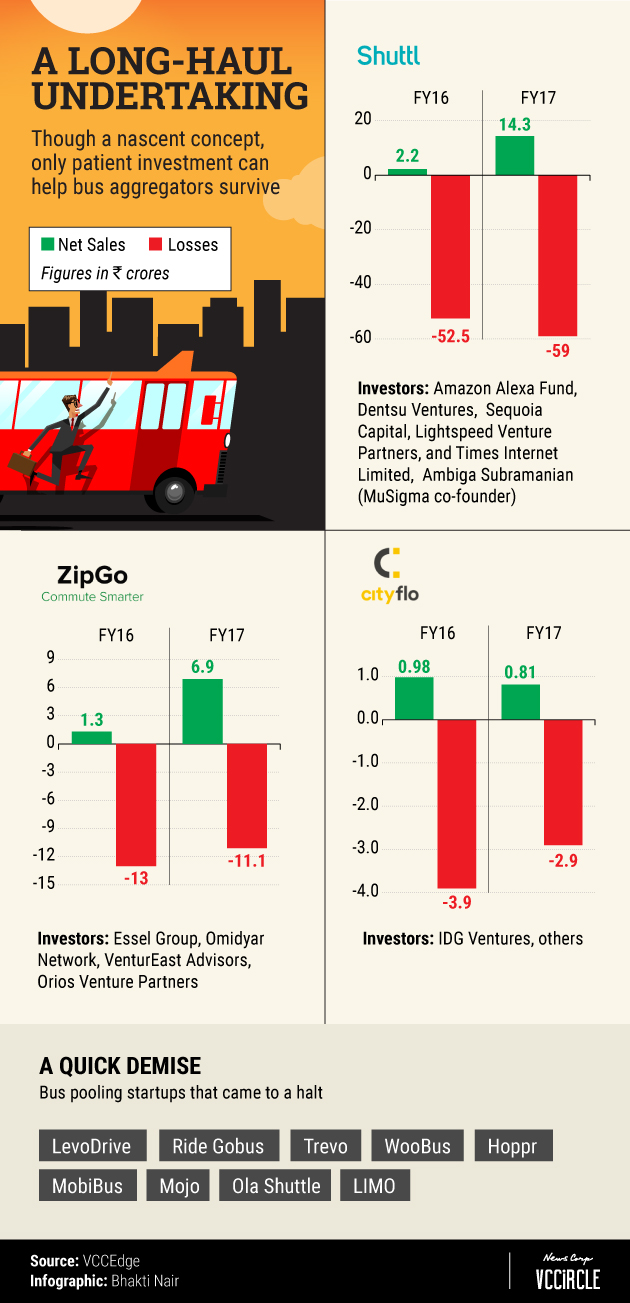

Early last month, bus aggregation platform ZipGo snagged more than $40 million in an uncharacteristically large Series B funding round. The investor was Subhash Chandra-led Essel Group, which committed to pump in the money through Essel Green Mobility Ltd. The deal signalled that despite recent upheavals in the nascent bus aggregation services business, it’s far from the end of the road for startups looking to tap into a potentially massive opportunity.

In India, there is no shortage of takers for buses as a mode of public transport. However, the availability of buses for general passengers falls far short of the demand—just four buses for every 10,000 people. Notably, the majority of these buses are privately owned. Out of the 19 lakh buses in the country, only 2.8 lakh are run by state transport undertakings. Add minibuses, minivans and maxi-cabs to the equation and a staggering number of vehicles make up the largely unorganised market. In a country where 90% of the population depends on public transport, that presents a big problem and the sector is ripe for disruption along the lines of the cab aggregation services run by players such as Ola and Uber.

ZipGo, owned by Bengaluru-based ZipGo Technologies Pvt. Ltd, isn’t the only startup in the space to raise capital in recent months on the back of this untapped opportunity. In July, Gurugram-based Shuttl raised $11 million in a Series B funding round led by e-commerce giant Amazon’s Alexa Fund and Japan’s Dentsu Ventures. Other investors in the startup, operated by Super Highway Labs Pvt. Ltd, include Sequoia Capital India, Lightspeed Venture Partners, Times Internet Limited and MuSigma co-founder Ambiga Subramanian.

Smaller players in the fray include Mumbai-based CityFlo, which raised a seed round of $750,000 from IDG Ventures and an unnamed investor, and Hyderabad-based EasyCommute, which raised $150,000 from undisclosed investors.

Challenges amidst an opportunity

The fledgling sector suffered a setback earlier this year when ANI Technologies Pvt. Ltd, the Bengaluru-based company that runs Ola, abruptly shut down its bus aggregator platform Ola Shuttle in February this year.

The company had launched the service in 2015 and expanded it rapidly across 10 cities. As part of an aggressive growth strategy, it offered hefty discounts to commuters and higher rates to bus operators.

Earlier, Mumbai-based LIMO, one of the first bus aggregation players to enter the market, shut down operations in November 2016. Negative investor sentiment aided largely by the general funding slowdown led to LIMO shutting shop.

In a recent interaction with TechCircle, the startup’s co-founder Siddharth Sharma said pressure from investors forces funded players in this segment to focus on scale rather than building a network, which is expensive and requires long-term commitment.

“These are very early days for the industry,” Shuttl co-founder Amit Singh told TechCircle. “Innovations in the cab aggregation model, which started in the US, got replicated in India pretty fast. However, the bus aggregation model started about 6-7 years later. Secondly, people who use public transport were not really equipped with smartphones and internet connectivity at the beginning. These factors really make it hard for players to get that initial traction,”

Indeed, the bus aggregation market presents a somewhat unique challenge for local entrepreneurs building consumer internet businesses. Traditionally, most consumer internet businesses in the country from ride-hailing to food delivery to e-commerce have replicated established global business models. There aren’t any globally successful templates available yet for the bus aggregation business.

Even the global examples that exist are early in their own development—Didi in China, Grabshuttle, ShareTransport and Beeline in Singapore and Chariot in San Francisco.

“A major challenge for bus aggregators is to fight the perception that buses are cheap,” said the founder of a bus aggregation startup that recently suspended operations. “Countries like India and China have a number of large cities with a population of over a million and are ideal for bus pooling. But the tech-enabled aggregators can only survive if they charge more premium rates when compared to public transport and increase the margins.”

What compounds the problem is that public transport has traditionally been a heavily subsidised sector, and therefore, establishing a realistic pricing structure is a monumental challenge.

Another hurdle is customer acquisition. Unlike a cab or restaurant aggregation startup, the marketing for bus aggregation services has to be much more distinct. Specially-designed programmes and campaigns such as referrals can work better than a TV or print commercial.

For these firms, plying on the most effective routes is a gradual work-in-progress and depends on insightful data gathering. Companies are yet to figure out ways to make optimum use of their assets, which in this case are buses, to reduce costs as they can run only during peak hours and often lie unused during the rest of the day.

The players that survived

ZipGo and Shuttl currently lead the market both in terms of capital raised and their scale of operations.

ZipGo offers intra-city and inter-city services for individuals and corporates. During its last funding round, the company said it will transition to a 100% electric fleet. It currently operates in Bengaluru, Delhi-NCR, Hyderabad, Jaipur and Mumbai. Venture capital firms Omidyar Network, VenturEast Advisors and Orios Venture Partners are the other investors in the firm.

Shuttl operates around 900 buses, averaging around 50,000 rides a day primarily around Delhi-NCR. The company has expanded to Kolkata recently.

ZipGo, Shuttl and its peers are working on different strategies to get around the challenges of the sector. For instance, they are strengthening their corporate and rental businesses to put their fleets into better use.

“We ensure an MBG (minimum business guaranteed) to vehicle owners with an incentive based on the performance, punctuality and driver rating,” said Rahul Jain, co-founder and CEO of EasyCommute. “To ensure that business is economically viable each day, we work on multiple fronts like ensuring daily demand on a particular route, guaranteeing that the first and last pickup and drop happens near a customer’s home to avoid unproductive kilometres.”

The company claims to be doing about 5,000 rides a day in Hyderabad with 180 active vehicles on the platform.

Bus aggregators are also building strong technology infrastructure to improve various elements such as estimated time of arrival (ETA), route optimisation, area-focused demand analysis and commuter travel patterns, better pickup and drop destinations to avoid multiple hops for users and to ensure minimum business for vehicle owners.

For example, Shuttl is working on improving its technology to ensure more accurate estimated times of arrival, while EasyCommute has created a tool named CityMapper, built in-house, to understand city geographies and to map specific locations such as SEZ hubs, government offices, tech parks and large residential societies. The system learns the travel pattern of commuters and adjusts the timings to help the company decide on the frequency of shuttles.

Last-mile connectivity, however, remains a critical missing link in the bus aggregation model. Unlike cabs, commuters have to travel to the pickup and drop points to board a bus, and this can create a mental block in users, thereby slowing adoption.

As a result, bus aggregators are working on forging strategic partnerships with last-mile connectivity players such as bicycle-sharing companies to further popularise the concept and change public perception for the better.

Meanwhile, some aggregators have already begun working with automobile manufacturers to make buses ‘sharing friendly’, integrating them with in-built hardware and software solutions so that the vehicles are ready to be part of the tech-enabled shared economy in the future.

Companies offering ride-hailing services for buses have also partnered with public-transport ticketing and mobility solutions such as Ridlr, the company that Ola acquired in April this year. Firms such as SnapCommute, Zophop, GoBengaluru and Moovit offer information on bus and train routes, let users book tickets for public transport besides giving them traffic updates.

Regulatory hurdles

Bus aggregators have a long way to go before they can iron out all the challenges they face. The obstacles are further compounded by the fact that investor interest in the sector isn’t as robust as it is in the cab aggregation business. That may change as the sector matures.

“The market segment is very different for both the products (cabs and buses),” said Jaspal Singh, co-founder of research and advisory firm Valoriser Consultants.

“There will be a good opportunity to cross-sell the services. Ola wanted to shift its focus back to the main business. Further, they struggled with the regulatory environment for a long time and decided to close the unit till there is less ambiguity in the law. Ola may come back in this segment after the regulatory environment improves,”

State governments have a monopoly in the bus market in India. City buses operate under the stage carriage permit. However, the majority of the state governments are yet to finalise their policies on regulating app-based transportation services. Bus aggregators are hoping that the regulations will catch up in time to meet the increasing demand.