Can India’s street-smart logistics startups scale the final frontier?

Entrepreneurs cutting across traditional and tech-enabled logistics firms agree on one thing - it’s a good business to be in. But success hasn’t come easy for the modern lot. The sheer size of the market was such that when technology began penetrating traditional businesses, logistics was a natural favourite. Players in the online logistics space have since ridden a roller coaster of experimentation and course correction before arriving at a point of relative stability. Now, with a crop of clear leaders emerging, achieving scale is the next frontier for logistics-tech startups.

But let’s begin with the bloodbath that came before.

Easy to start, difficult to scale

On paper, the scope was enormous, the business was easy to understand and the entry barrier was low. This attracted a herd of me-too startups to the space. They all wanted to tap the vast opportunity by addressing some of the core inefficiencies in the sector. With this mind, a number of firms offered solutions such as price optimisation, easy payments and documentation processes, and reducing empty-truck miles.

Then reality hit. The logistics sector has long been plagued by several complexities - some of them legacy issues - ranging from wafer-thin margins to frequent delays, poor transparency and long working hours.

In the end, the many me-toos failed to identify these challenges and ended up becoming also-rans.

Investors also had to learn the hard way. A bevy of venture capital firms had sought to place bets on a segment which they thought could produce the next unicorn in an emerging startup ecosystem. However, the complexities of the space hurt their prospects too and India is still to produce a logistics-tech startup valued at $1 billion or more.

“Investors and entrepreneurs failed to foresee the hidden execution complexities involved and that killed a lot of businesses,” says Mithun Srivatsa, co-founder and chief executive officer of intra-city logistics marketplace Blowhorn. “It’s very easy to start, but very difficult to scale. The number of failed startups is much larger.”

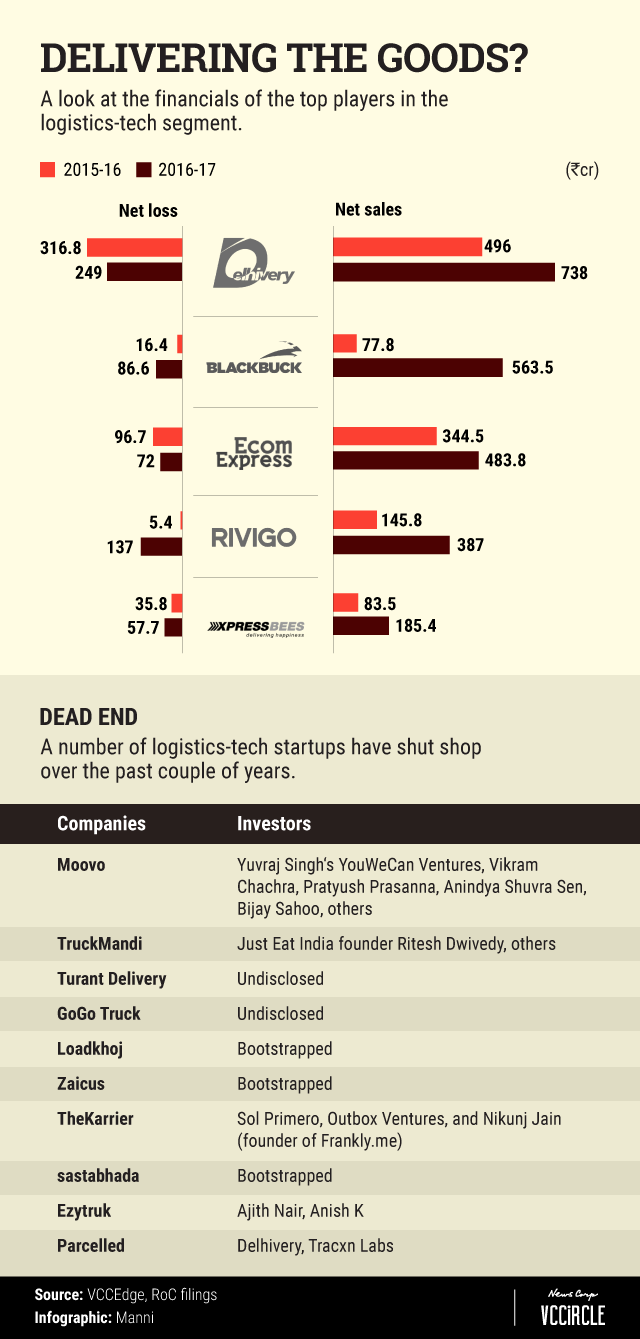

That’s not an exaggeration. At least 11 logistics-tech startups including Turant Delivery, GoGo Truck, Loadkhoj and Truckmandi have shut shop over the past two years (see graphic).

The majority of these startups were unable to offer a price advantage to their clients and struggled to move firms from the unorganised sector to an organised setup.

To be fair, not every startup had the financial cushion to experiment or time on their side to build sophisticated technology that could bring about a considerable difference in margins. Additionally, the credit-based business model was not financially viable for many of these startups.

“The organised players including startups have to play with lower margin structures vis-à-vis unorganised players,” says Revant Bhate, partner at VC firm Kalaari Capital's seed fund Kstart. Kalaari invested in transportation technology startup ElasticRun last year.

“Unless there is a significant return on investment, people don’t move from unorganised to organised players,” he added.

Another problem was that even larger businesses, in general, were slow to implement technology in the supply chain and among their procurement teams. Bhate feels this prevented early-stage businesses from scaling up as they went deeper into the ecosystem.

Survival of the fittest

Now, for the startups that survived to tell the tale, it’s all about scale.

“The traditional companies are large. Startups are really tiny when compared to them,” says Srivatsa of Blowhorn. “So the new tech-based startups like us will have to figure out as to how we could scale faster while keeping profitability in mind. For the next one or two years, companies will focus on scaling.”

The segment is broadly divided into four categories. The likes of Blowhorn and Flipkart-backed BlackBuck cater to large, traditional businesses by offering them last-mile and hub delivery services. Others like Trukky focus on small and medium enterprises. A major category is e-commerce logistics, where companies such as Delhivery and Shadowfax serve the first- and last-mile needs of Flipkart, Amazon and other online marketplaces. A fourth category is home and corporate relocation services.

While the majority of these companies aggregate third-party truckers to offer full-stack solutions, a few such as Rivigo own either 100% or a portion of their fleet.

In the business-to-business (B2B) segment, Rivigo, which also has a truck marketplace subsidiary called Vyom, was valued at $900 million in its most recent funding round where it raised $50 million, putting it on course for unicorn billing.

Delhivery, which is backed by Times Internet, Tiger Global and a couple of private equity investors, recently hired investment bankers to help make it the first tech-enabled logistics firm in the country to go public.

Apart from Rivigo and Delhivery, online marketplace BlackBuck, e-commerce specialist Ecom Express and Alibaba-backed Xpressbees have also been incurring heavy losses amid efforts to grow (see graph).

That said, Delhivery’s plan for an initial public offering reportedly came on the back of it turning profitable. However, this is not official as the firm is yet to file its financials for 2017-18.

“The remaining players all believe that once they have the required scale, they could do a few tweaks here and there to find profitability,” says Sikander AM, managing director of Sitics Logistic Solutions, a third-party logistics firm. “We should expect these startups to bleed for a few more years.”

New horizons

Sikander believes many players are likely to explore an integrated intra- and inter-city approach in the quest for scale while focusing more on the hyperlocal market, where the potential is huge.

“Most of the players in the segment are still focusing on the Tier-I cities, so I expect many of them to go deeper into Tier-II and III cities to expand their horizons,” he says.

But a key challenge remains: organising an extremely fragmented sector. There are not many large fleet owners in the country and the arrival of mini-trucks is a relatively new phenomenon.

“Digital logistics firms will have to make patient investments not just on customers, but also on truckers to get them used to online processes and payments,” says Subhasish Das, co-founder and chief executive of aggregator Trukky. “There needs to be a behavioural change on the customer side as well as on the transporter’s side.”

In the e-commerce logistics space, companies eyeing growth are looking to diversify their operations to multiple avenues. This, even as e-commerce giants Flipkart and Amazon pour large sums into their own logistics arms - eKart and Amazon Transportation Services, respectively - as they aim to cut costs.

According to a KPMG report, India’s e-commerce logistics market stood at $460 million in 2016 and is expected to grow at a compounded annual growth rate of 48% to reach $2.2 billion by 2020.

Though e-commerce remains their primary focus, a number of top players have initiated efforts to penetrate deeper into Tier-2 cities while turning their attention to other B2B segments to grow.

Focus on tech

In addition, logistics startups across the board are integrating their offerings and strengthening their tech prowess to influence margins.

“Given the thin margins in this business, you won’t make profits unless you are a very efficient operator. Technology can play a great role here in helping you widen your margins,” says Sitics’ Sikander.

The emergence of a number of logistics-focussed software firms such as Loadshare, Locus, Loginext, and Shipsy are helping players digitise procurement and supply chain processes.

They provide analytics-driven insights, automated smart dispatches, tracking services, fleet visualisation, geocoding and route deviation engines, among other services.

While the well-funded logistics startups develop such tech prowess in-house, the marketplaces that focus on aggregation rather than offering end-to-end solutions are increasingly subscribing to such enterprise solutions to rationalise their operations to manage order density as well as optimising network and routes.

“A lot of aggregators are now identifying that only an effective tech play can help them scale and become profitable,” says Prateek Goyal, investment professional at equity crowdfunding platform 1Crowd.

He added that many startups such as Rivigo, Soppa and Trukky are also exploring the benefits of a shared economy, or ‘load sharing’ in logistics parlance. This enables customers to transport shipments in small quantities and pay only for the space occupied in a consignment.

One boon for the sector could be the Goods and Services Tax. GST’s growing pains did slow the industry down early on, especially the SME and intra-city segments. But the long-term benefits of the “one nation, one tax” system are starting to look promising.

Trukky’s Das says the regulatory reforms are already yielding positive results.

“A lot of business that used to go to the unorganised sector is coming to the organised sector,” he says.

Kalaari’s Bhate is pinning his hopes on the regulatory advancements such as GST to help organise the space and lead to maturity over the next three to five years.

Meanwhile, two of India’s biggest automobile firms clearly believe that the sector holds promise.

Mahindra and Mahindra said in February that it would merge SmartShift, an on-demand logistics platform connecting cargo owners and transporters, with truck rental startup Porter, a portfolio firm.

And last month, Tata Motors Finance Holdings, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Tata Motors Ltd, picked up a significant minority stake in online freight aggregator TruckEasy.

Online logistics is not an open road, so it's now up to the big players to use their street-smarts to keep the engine running.